(Appears on the Arabic edition, translated to Arabic)

Proudly presenting the third book in our new digital library series of Jewish and Israeli masterpieces translated into Arabic. Available free of charge at the Dangoor Centre site: Library

Yoel Collick

It has been nearly two decades since The Case for Israel was first published. During this time, while much has changed, much has also stayed the same. Like any historical process, the seeming contradictions of change and continuity are in fact two sides of the same coin. What has changed can be explained by what has stayed the same. So, what has remained the same?

What has remained the same, is the continuation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the fact that the Palestinians remain stateless. Notwithstanding substantial autonomy enjoyed by most Palestinians in the West Bank, Israeli military occupation and settlement expansion persists. Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza alike continue to live under corrupt and unaccountable rulers who consistently fail to improve the livelihoods of populations under their care. Meanwhile, Palestinians considered refugees by UNWRA throughout the rest of the Middle East continue to face discrimination by Arab states that refuse to integrate them into the political and social fabric of their countries, preferring them to live in squalor at worst, or without equal access to healthcare, employment or citizenship rights at best. Some 1.5 million Palestinians continue to live in refugee camps decades after they – or, rather, mainly their parents or grandparents – first lost their homes.

Reported at Times of Israel

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-case-for-israel-revisited/

What has remained the same for Israel is that it continues to face security threats incomparable to any democracy on the planet, posed by hostile neighbours including terror groups on its borders and a state seeking nuclear weapons promising to wipe it off the map. Israel remains unrecognised by, and technically at war with, many of the Muslim and Arab states that surround it. Its security deterrent and the personal sacrifice of thousands of Israelis remain the sole reason for its continued existence. Israel’s security apparatus and civilians alike face relentless acts of terrorism throughout the country. Yet, despite all these tensions, Israel remains a regional economic powerhouse and a beacon of democracy in the Middle East, with free and fair elections, checks and balances, and a vibrant, independent press. Israel continues to conduct its security responses with restraint, proportionality, and the utmost consideration for preserving human life, with its potential excesses curtailed by the country’s democratic mechanisms and reverence to the rule of law.

The nature of the conflict remains much the same, too. Israel’s leaders have continued to offer peace, while their Palestinian counterparts have continued to refuse their offers. Just as Israel gave up the Sinai in exchange for peace with Egypt in 1979, so, too, in 2005, two years after The Case for Israel was first published, Israel made a substantial unilateral gesture for peace by withdrawing from Gaza and uprooting four settlements in the West Bank. It is a gesture for which millions of Israeli civilians within range of the rockets fired out of the Strip continue to pay the price. Just as Ehud Barak’s offer of Palestinian statehood to Yasser Arafat at Camp David in 2000 was rejected, so too Ehud Olmert made a similar offer to Mahmoud Abbas in 2008, but to no avail. Israel’s settlement freeze in 2009-2010 failed to assist faltering peace talks. During their tenures, Binyamin Netanyahu and Yair Lapid alike publicly called for dialogue with their counterpart in Ramallah, but in vain. The Israeli public consistently proves significantly more willing to make compromises for peace than the Palestinian public. More to the point, Israel’s overtures to peace have not encouraged conciliation, but rather induced more Palestinian violence, with Israeli civilians facing bombing attacks on buses and in cafeterias in the wake of Camp David in 2000, and intermittent rocket fire from Gaza since the 2005 disengagement until today.

Meanwhile, internationally, Israel continues to be subject to double standards driven by antisemitism operating under the guise of anti-Zionism. Despite countless states with more egregious human rights violations, not least in the Arab world, the Jewish State is repeatedly singled out for international condemnation and sanctions, condemned by more United Nations resolutions than all other countries combined. The industry of lies about Israel assiduously continues to manufacture more libellous claims, from harvesting organs to genocide, fuelling the conflict at home and delegitimising Israel abroad. The circumstances of the founding of the Jewish State and its history are still cynically distorted. Israel continues to be erroneously blamed for the deaths of Palestinians who are either alleged to have been bystanders but were in fact combatants, or were in fact caused by Palestinian military activities. All of this has stayed the same.

What has changed, however, is that a dwindling number of Israelis and Palestinians believe that peace is possible, while fewer and fewer support the two-state solution. This change, however, is a regrettable consequence of the continuationof bloodshed. Professor Dershowitz, a long-time proponent of the two-state solution, acknowledges the fragility of its support in the outset of his book. “To be sure”, he writes, “the poll numbers in favor of a two-state solution vary over time, especially according to circumstance. In times of violent conflict, more Israelis and more Palestinians reject compromise”. It is also undoubtedly true that the persistence of violent conflict encourages precisely this rejection. Political radicalisation and mutual mistrust have, in recent years, grown to new lamentable heights. The flailing Fatah movement and the Palestinian Authority show virtually no political will to recognise the Jewish State, even on paper, while extremist elements who openly call for the elimination of Israel such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad have enjoyed growing popularity at the PA’s expense. Indeed, the PA has been rapidly losing control over some of the most violent elements under its jurisdiction in places like Jenin and Nablus, whose efforts to build terror infrastructure go largely unimpeded.

Israeli society, too, has become more radical and hard-line in the face of constant terror attacks and assaults on its legitimacy, unparalleled by any other democracy in the world. In more recent years, no serious overtures to the Palestinians have been made, and calls to annex the West Bank and establish a Greater Israel have grown. Far-right politicians and activists who were once shunned as a radical, fringe element of Israeli society are now serious political actors. The political shift in Israel is not, however, solely related to the continuation of the conflict. Israeli liberalism is currently exposed to the same assault of populist forces that democracies are facing world over – from the United States and India to Sweden and Italy.

As such, this translated edition is undeniably provocative, but also has the potential to be constructive. Divided into concise chapters, each of which can be read on its own, The Case for Israel tackles, head on, the chief accusations against Israel that are deeply pervasive in the Arab world: that Zionism is colonial and imperialist, that the Jewish State was founded on an orchestrated policy of ethnic cleansing, that the Jews have exploited the Holocaust, that Israel is responsible for its wars with its neighbours, that it unjustly tortures Palestinians and engages in genocide, and that it is the world’s prime human rights violator.

The underlying messages of The Case for Israel are more pertinent today than ever. With the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court’s unjust decision to investigate “the situation in Palestine”, Professor Dershowitz’s warning that undue prejudice drives such decisions, that Israel is “the Jew among nations”, has taken on renewed importance. The book also reaffirms a much-needed reminder at a time when political extremism gains ground that a “resolution that recognizes the right of self-determination by Israelis as well as Palestinians is the only reasonable path to peace”.

Above all, however, The Case for Israel has renewed relevance considering one further area of change that has not been mentioned above. Recent years have witnessed a growing rapprochement between Israel and Arab and Muslim states, from Morocco and Sudan to the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain: a shift epitomised by the 2020 Abraham Accords and subsequent overt cooperation on a whole host of issues in defence, healthcare, industry, agriculture and more. As well as the threat posed by Iran, this geopolitical change is borne out of these states’ acknowledgment of Israel’s continued resilience, admiration for its innovative economy, and exhaustion with the Palestinians’ inability to make the necessary steps to bring an end to the conflict that had long dominated Israeli-Arab relations. Saudi Arabia’s Prince Bandar’s criticism of Arafat’s “crime” in rejecting Barak’s offer at Camp David, quoted by Professor Dershowitz in the book, was a sign that patience was thinning. “I hope you remember, sir, what I told you”, Bandar had said. “If we lose this opportunity, it is going to be a crime.” Many Arab States have decided that they are no longer willing to be party to the crime.

They have, instead, made their own ‘Case for Israel’, built on geopolitical realities. This ‘case’ however, which has no interest in tackling some of the fundamentals in the Arab narrative about Israel, is not enough to convince the Arab public at large, which broadly continues to shirk any notion of conciliation with Israel. Only by questioning deep-seated prejudices and assumptions can the Arab public – including, of course, the Palestinians themselves – follow in the footsteps of some of its leadership in making peace with Israel. The Case for Israel, in tackling precisely these matters, is an invaluable tool to help enable this.

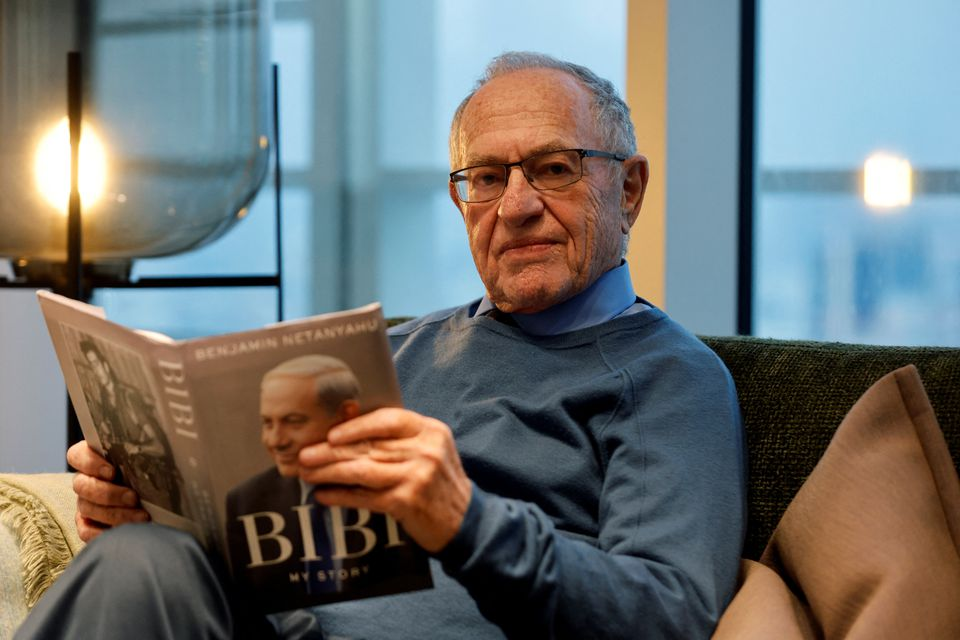

Professor Dershowitz’s reputation as one of the world’s foremost legal experts and articulate advocates of Israel, who nonetheless openly expresses opposition to certain Israeli policies, renders this book worthy of attention to Arab readers. It should appeal to the curiosity, and indeed fierce scepticism, of many who may believe that there is no such thing as a case for Israel. Its subject matters, while provocative, should draw readers in, precisely because it addresses such topics in such a direct manner. The book will certainly challenge many of its readers.

It might also influence them. In 2005, one young British Muslim by the name of Kasim Hafeez, encountered The Case for Israel in a bookstore. “I bought it so I could disprove it”, he said. Hafeez had grown up in a devout Muslim household and during his youth embarked on a journey of radicalisation. On that fateful day in the bookstore, he was ready to be a mujahid for Palestine. The contents of the book shocked him. “Here I was, ready to go blow myself up, being confronted by reading material which made me doubt the basis of my long-held beliefs.” The book encouraged him to read more and even visit Israel himself. As a result, while continuing to support Palestinian rights, he is now a pro-Israel activist.

Rendering The Case for Israel in Arabic has the potential to create similar positive change on a far greater scale. The book can help bring about the change that is desperately needed in the Arab world: an end to the culture of rejection and prejudice. That, however, is down to the readers themselves.

Yoel Collick is a graduate of the University of Cambridge where he studied History and Political Thought, and is a writer and researcher of Jewish, Israeli and Middle Eastern affairs based in Jerusalem.