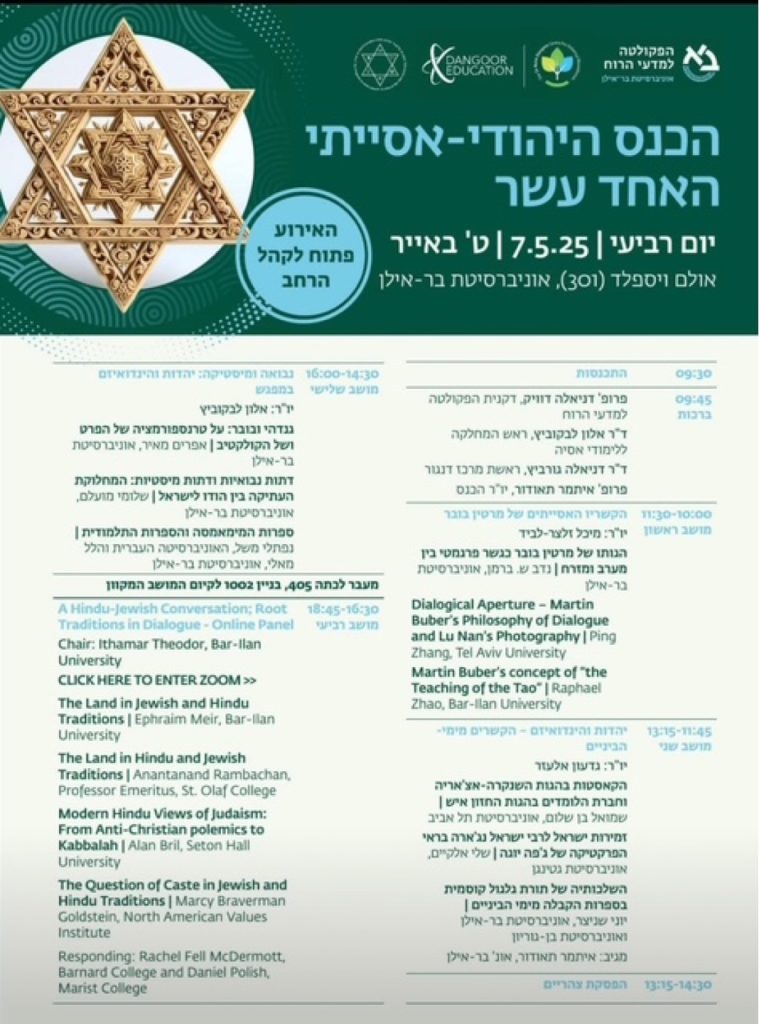

On May 7, Bar-Ilan University proudly hosted the 11th Jewish-Asian Conference, an annual gathering dedicated to exploring the rich intersections of Jewish and Asian thought. This year’s event, held under the auspices of the Sir Naim Dangoor Centre for Universal Monotheism and Dangoor Education, offered fresh insights into comparative philosophy, interreligious dialogue, and cross-cultural exchange.

The opening session, titled “Martin Buber in Asian Contexts,” unveiled previously overlooked connections between Buber’s philosophy and classical Chinese thought. Scholars presented compelling evidence that the Daoist concept of Wu-Wei (non-action) significantly influenced Buber’s dialogical philosophy. They argued that the Buberian dialogue, which emphasizes presence and openness over outcomes, echoes the Daoist ethos of detachment from the fruits of action. Furthermore, Buber’s vision of Zionism was discussed not as a Western or Eastern project, but as a cultural bridge between the two—a theme highly relevant to the conference’s broader mission.

The second session explored devotional practices in Hinduism and Judaism, focusing on the chanting of divine names. While direct repetition of God’s names is more central in Hindu traditions, the session highlighted parallel, albeit more implicit, practices within Jewish liturgy. The discussion illuminated shared spiritual expressions that transcend cultural boundaries.

In the third session, three contributors to the recent volume “Prophecy and Mysticism – Judaism and Hinduism in Encounter” engaged in a rich dialogue about the theological and ethical intersections between Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Buber. The panel proposed a potential Gandhian-Buberian synthesis, grounded in a shared commitment to spiritual activism. The session also offered a critical engagement with Robert Zehner’s theory of religion and concluded with the introduction of an innovative concept—Talmudu-Mimamsa—which posits a deep methodological affinity between Talmudic interpretation and the Hindu Mimamsa tradition.

The final session, conducted online, focused on a newly published comparative volume on Jewish-Hindu thought. Esteemed scholars from Israel and the United States participated in this international dialogue, which examined divergent approaches to the sanctity of land in both traditions and proposed new avenues for comparative analysis.

The Dangoor Centre is honored to have supported this intellectually vibrant and culturally significant event. Prof. Ithamar theodor, The conference director concluded the event with kind words of gratitude: “We extend our deepest gratitude to Dangoor Education and the Sir Naim Dangoor Centre for Universal Monotheism for their generous sponsorship, which continues to make such scholarly exchange possible”.

Dr. Danielle Gurevich opening words:

A few years ago, a dramatic controversy erupted around the ritual of hair-cutting and shaving at the Tirupati Temple in Tirumala (Andhra Pradesh) in southern India—a controversy that sent shockwaves through religious communities worldwide, including in Israel, the United States, and Europe.

It is well known that the finest wigs—those costing $1,000 and more—are made in India from human hair. A significant portion of this hair comes from Tirupati, where pilgrims are required to shave their heads as part of their religious devotion. Once collected, the hair is sold to companies that produce wigs for women—wigs that are especially popular among ultra-Orthodox Jewish women. One day, a group of rabbis issued a ruling stating that wigs made from Tirupati hair were the product of idol worship, and the news caused an uproar.

Rabbis in England, Israel, and the United States declared that this hair was “tikrovet avodah zarah”—an offering to idolatry—and therefore prohibited for any use. This ruling meant that one was forbidden even to touch such wigs, leading to the burning of thousands of highly valuable wigs.

Scholarly and well-argued responses were published, focusing on the halakhic (Jewish legal) aspects of the issue, with the overwhelming majority concluding that the wigs must be destroyed. Others, taking a more lenient approach, suggested replacing them—a proposal that was not always practical.

However, none of these scholars possessed any real knowledge of Indian religion, culture, or languages, and none had ever visited India. Only a small number of halakhic authorities ruled that these wigs could be worn, and those who sought a lenient solution did so by identifying legal loopholes in Jewish law, rather than out of any understanding of Indian practices.

There was, however, one notable exception: Rabbi Professor Daniel Sperber, who delved deeply into the controversy and conducted his own research. He explained that millions of Hindus visit Tirupati every year—up to 20,000 a day—resulting in massive quantities of hair. When the temple authorities realized the hair could serve as an additional source of income, they began selling it to wig manufacturers.

Sperber investigated and found that pilgrims shave their heads before entering the temple, depositing the hair outside its entrance. Since the shaving takes place outside the temple as part of a preparatory and purifying process, and is not part of the religious ritual itself, his conclusion was that wearing wigs made from this hair should not be prohibited. His ruling was ultimately accepted.

My name is Dr. Danielle Gurevitch. I founded the Sir Naim Dangoor Centre for Universal Monotheism in 2008, an institution devoted entirely to interreligious and intercultural dialogue—just as illustrated by the example I have shared with you today.

Professor Itamar Theodor, my friend and a faculty member in the Department of Asian Studies, speaks this same language of understanding—which is one of the reasons I so value his partnership (among many others).

The story I shared about the “wig affair,” in essence, encapsulates the profound importance of a Jewish-Asian conference: to dispel ignorance, fears, and misunderstandings, and to challenge, even diminish, the Western sense of superiority over other cultures. Every culture possesses its own system of symbolic language, and it is our responsibility to combat misinterpretations of gestures, words, and behaviors. A conference such as this serves as a foremost cultural translator.

At this very moment, Sperber’s book, “What the West Can Learn from the East”—which I have edited—is going to press, to be published as part of the Dangoor Center’s “History of Ideas” series. The book addresses the translation of Eastern culture for Western audiences. Most of you are likely familiar with Sperber. For sixty years, he traveled repeatedly to India in various capacities—from wanderer to Chief Rabbi of Calcutta, and, in practice, of India as a whole. He is deeply in love with the East, and especially with India. With great humility, he befriended local religious leaders, learned from them, and, above all, listened—something that should not be taken for granted.

Over the course of six decades, Sperber studied Hindu thought, theory, and practice, as well as Jainism and Buddhism, striving to clarify points of uncertainty, dispel common doubts, and correct deeply rooted misconceptions and mistaken interpretations.

Among his groundbreaking conclusions is the view that Hinduism should not be regarded, as it is from the outside, as polytheistic or idolatrous, but rather as a legitimate monotheistic religion, grounded in the principle of “unity in multiplicity.” He provocatively asks: Is there not also, within Judaism, veneration of objects? What, for example, is the bronze serpent after the Ten Commandments were given and set in a high place? The answer, according to the Mishnah, is that only because Israel looked upward were they redeemed—so, in essence, it is the same.

Sperber is a remarkable individual; there are few like him. His deep understanding has proven to have significant practical implications, which can be seen as a major halakhic innovation within the Orthodox community. He himself regards his ruling on Hinduism as one of the greatest challenges he faced in his professional life.

And then there is you: the scholars of academia. In conferences like this, and through your academic publications, you create a platform for dialogue, sharing knowledge, and bridging interfaith misconceptions. You contribute to a deeper understanding between people and the divine in our modern era. You remind us all of the enduring importance and impact of the humanities—teaching humility and consideration toward other cultures and religions, which is the key to growth and progress. I wish you a successful and fruitful conference.